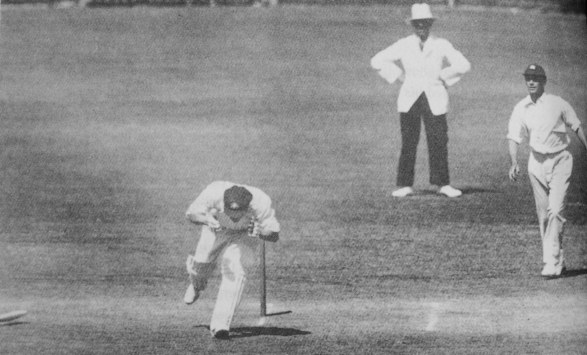

Stan McCabe rubs his chest after being struck by a ball.

But for the second Test at Sydney, Australia rejigged its team, debuting two more players and dropping Bradman to twelfth man. It didn't help, with England again dominating and winning by a huge 8 wickets. In Australia's first innings, one of their best batsman, Bill Ponsford, was struck on the left hand by a Larwood delivery, fracturing the hand and forcing him to sit out the rest of the match.

It was in Sydney that Jardine's demeanor and attitude towards the Australian public began to appear. Educated at Oxford, Jardine habitually wore his Oxford Harlequin cap on the cricket field, marking him as one apart from his team mates, and one who flaunted his aristocracy. The Australian crowds jeered him for this display of ostentation. During an earlier warm-up match against Victoria in which this occurred, Australian player Hunter Hendry offered his sympathies for the jeers Jardine was receiving. Jardine replied, "All Australians are uneducated, and an unruly mob."

By the time the team reached Sydney for the second Test, Jardine was systematically being jeered by the crowd. His team mate Patsy Hendren observed, "They don't seem to like you very much over here, Mr Jardine." Jardine replied, "It's f***ing mutual." Fielding at third man, right in front of the Sydney Cricket Ground Hill, Jardine endured the taunts of the crowd without paying them any notice, until he left the field for the last time. Then he turned his head to the crowd, spat on the ground, and walked off.

With Ponsford still injured, Australia brought Bradman back into the side for the third Test at Melbourne. Batting at number 6, he scored 79 and 112 as Australia fought England more effectively than at any time earlier in the series. England scraped home in a thrilling 3 wicket victory, however.

The fourth Test at Adelaide was even closer. Australia chased 349 to win in the final innings, and Bradman almost steered them home with a middle-order 58, at which he was run out. The tail then collapsed and Australia fell a tantalising 12 runs short, giving England their fourth straight win.

The fifth Test at Melbourne was a marathon, played without time limit over 8 gruelling days. England took over two days to post 519. Bradman top-scored with 123 in Australia's response of 491 by the end of day 5. England scored 257, setting Australia 286 to win. Bradman was at the crease on 37 not out with his captain John Ryder as they finally vanquished the Englishmen by 5 wickets.

England had dominated the series. Bradman appeared to be a promising young batsman, Larwood a decent bowler, and Jardine an imperious snob. But there was scarcely a hint of what was to follow.

But in Australia's first innings of the first Test at Nottingham, Bradman faltered, scoring only 8 as Australia struggled to 144 in reply to England's 270. England added another 302 in their second innings, setting Australia 429 to win. This time Bradman fired, top-scoring with 131, but the target was simply too much and Australia lost by 93 runs.

The second Test at Lord's was a fast-scoring affair. England put 425 runs on the board in quick time. Bill Woodfull and Bill Ponsford opened for Australia, piling on 162 for the first wicket. When Ponsford was finally out, Bradman strode to the crease, and English cricket was never the same again. He and Woodfull added 231 runs before Woodfull fell for 155. Bradman then continued his slaughter of the English attack by contributing another 100 runs in a 192-run partnership with Alan Kippax. When Bradman was caught out, he had scored 254, having batted only a few minutes more than Woodfull and having faced fewer balls. Where Woodfull had scored 9 fours, Bradman had bludgeoned the bowlers for 25. Australia were 160 runs in the lead, with only 3 wickets down. Eventually they declared at 6/729. England's batsman fought back valiantly, putting together 375, but with Australia's mammoth first-innings lead they only needed 72 runs to win. This was dispatched with ease and Australia won by 7 wickets.

In the third Test at Leeds, Bradman went on an even more devastating rampage. He shared partnerships of 192 with Woodfull and 229 with Kippax as he raced to 334 - at that time the highest individual Test innings, and a score bettered only seven times since. Bradman struck an amazing 46 fours in his innings, and scored nearly 60% of Australia's total of 566. England fell for 391 and (being a four-day match) Woodfull asked them to follow-on. The match ended in a draw with England 3 wickets down and still 80 runs short of making Australia bat again.

The fourth Test at Manchester was rained out on the fourth day, being drawn with England's first innings still incomplete at 8/251, well behind Australia's 345. Bradman contributed only 18, but he wasn't done with England yet.

Although Australia had dominated the summer, the series still stood at 1-1 when the fifth Test began at Kennington Oval in London. England won the toss and decided to bat, assembling a respectable 405. Again Woodfull and Ponsford set Australia flying with a 159-run opening stand. Bradman then scored 232, battling a sometimes unpredictable bounce on a damp pitch, and putting Australia 165 runs in the lead when Harold Larwood had him out caught by George Duckworth. It was Larwood's only wicket of the match. Australia reached 695. England struggled to even force Australia to have to bat again, but fell to a 7-wicket haul by Percival Hornibrook and lost by an innings and 39 runs.

Australia had won the series and the Ashes. They played five more matches on the tour, with Bradman scoring 205 not out against Kent and 96 against H.D.G. Leveson-Gower's XI. By the time the Australians left England, Bradman had scored 2,960 first class runs on the tour, at an average of 98.67. In the Tests, he had fared even better, with 974 runs at an astounding average of 139.14. That 974 aggregate is a series record that stands to this day, despite the existence of later six-Test series. Clearly, this was a batsman to be reckoned with. England had to do something drastic if they were to have any chance of regaining the Ashes in the next series.

Yes, I think that can be done. It's better to rely on speed and accuracy than anything else when bowling to Bradman because he murders any loose stuff.Together, they hatched a plan. With Larwood and Voce bowling at Bradman's body, they would pull most of the fielders on to the leg side, ready to take any catches that might pop up off the bat used to fend the ball away. Jardine questioned the open off-side field, but Carr replied that Larwood was so accurate that was no need for concern. And so fast leg theory was born.

Later, the MCC gathered a meeting in its committee room to view film of the Test series. Jardine noticed that Bradman looked decidedly uncomfortable in the fifth Test against the unpredictable bounce of the wet pitch, particularly rising balls flying near his body (as any batsman would). Seeing this exhibition of only too human frailty as the chink in the armour of a man until now considered to be more godlike than mortal on the field, Jardine suddenly exclaimed, "I've got it! He's yellow!"

Over the next two years Larwood and Voce practised their technique in county matches, as did Bill Bowes for Yorkshire. The three terrorised their oppositions, and several batsmen were struck by the ball and injured. Fast leg theory - bowling fast rising balls at the body and stacking the leg side field - became almost commonplace and attracted some comment in the media, mostly negative. But batsmen continued to score runs as the bounce on soft English pitches was rather lifeless, and nobody considered the tactic effective or dangerous enough to particularly worry about.

Harold Larwood, Bill Voce, and Bill Bowes formed the backbone of the touring party's bowling attack. On the 31-day voyage aboard the S.S. Orontes Jardine built up team spirit for the clash ahead, discussing the details of fast leg theory and telling his team that they must hate their Australian opposition. He instructed his team never to refer to Donald Bradman as "Don" or "Bradman", but to call him "the little bastard".

The night before the first warm-up match of the tour, in Perth, newspaper reporters for Sydney and Melbourne papers were eager to get Jardine's selected team for the game, to beat their deadlines in the eastern cities, two hours ahead. One pleaded with Jardine, "Sydney and Melbourne are waiting." Jardine responded, "Tell Sydney and Melbourne they can bloody well wait."

The English team drew their opening match against Western Australia. Jardine annoyed the match officials by turning up late to an official pitch inspection. They then drew a second match in Perth against a Combined Australian XI, in which Bradman played, scoring a meagre 3 and 10. The English team beat South Australia by an innings and 128 runs in Adelaide, then Victoria by an innings and 83 runs in Melbourne.

The next match was another warm-up against an Australian XI. Jardine took time off to go fishing and vice-captain Bob Wyatt commanded the Englishmen. Wyatt took the opportunity to put fast leg theory into action for the first time on Australian soil. The Australians were at first mystified as the fielders packed the leg side, but when the bowling followed them it soon became clear, to Bradman at least, what was happening. He had to dance around the crease and play unorthodox shots to avoid being hit by the fast balls aimed at his body. Bradman managed only 36 and 13 before being dismissed in both innings as the game was drawn. Bill Woodfull wasn't even that lucky, being struck on the chest by a bouncer from Larwood that held up play for 10 minutes while he recovered.

Media reaction was mixed. Bruce Harris wrote for the Standard back in England: "Provided that Larwood retains his present demon speed, the Bradman problem has been solved. Bradman dislikes supercharged fast bowling." But Hunter Hendry - who had offered his sympathies to Jardine as a player back in 1928-29 and was now writing for the Melbourne Truth - wrote:

Douglas Jardine, captain of all the bally old English cricketahs, went trout fishing while Larwood was trying to decapitate Don Bradman and Bill Woodfull. Now, just why did Mr Jardine go off hunting for trout?Hendry suggested it was so Jardine would escape any outcry over the tactic. And outcry there was, as other Australian reporters wrote scathing articles.

Bradman met with some delegates of the Board of Control for Cricket in Australia and voiced his concerns over the English tactics. They decided to reserve judgment until after the next match, against New South Wales in Sydney.

Before that match, in an incident witnessed by later New South Wales player and famous radio commentator Alan McGilvray, Jardine was asked for an autograph by a young fan. Jardine swept the fan away with "such arrogant disdain I was consumed with an instant dislike for him."

Larwood and Bowes were rested for the game against New South Wales, but Bill Voce continued the fast stuff aimed at the batsmen, and young Jack Fingleton wore over a dozen bruises on his body, sustained in his courageous innings of 119 not out, carrying the bat for NSW. After the game he was quoted as saying that he was "conscious of a hurt, and it was not because of the physical pummelling I had taken from Voce. It was the consciousness of a crashed ideal." Bradman had failed again under the barrage, as England defeated NSW by an innings and 44 runs.

Horrified letters poured into the Australian newspapers, with luminary names in cricket stating that never before had they seen such objectionable bowling. One called Jardine's tactics the moral equivalent of telling a football team to put the boot into an opposing player, others claimed English cricket had been tarnished and urged the Australians not to retaliate in kind. The Australian Board members, however, having reserved judgment after the previous game, now made their decision. Despite the evidence of Fingleton's battered body, they concluded the Englishmen were not deliberately bowling at the bodies of the batsmen.

The next match was the first Test against Australia. On a recreational boat trip on Sydney Harbour before the Test, the Englishmen were treated to the spectacular sight of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, opened earlier that year and the source of immense pride in a country ravaged by the Great Depression. As some Royal Australian Air Force planes flew over the bridge, Jardine snarled, "I wish they were Japs and I wish they'd bomb that bridge into their harbour."

This was the first Test series to be broadcast live on radio in Australia, so coverage was complete and instant to anyone within reach of a radio across the country. The journalists following the English tour had been discussing England's tactics in the pressrooms and tossed around some ideas on what to call the English bowling strategy. Nobody knows who first said it, but Hugh Buggy of the Melbourne Herald was the first to write it. His story in the Herald of 2 December, the dawn of the first Test, contained the word that described where those fast balls were aimed: bodyline.

Not all the Englishmen were in favour of the tactic though. On the morning of the Test, Jardine said to bowler Gubby Allen, "We all think you should bowl more bouncers, and with more fielders on the leg side." Allen replied, "Douglas, I have never done that, and it's not the way I want to play cricket."

Bill Woodfull won the toss and elected to bat first. The pitch was tinged with green and the sixth ball of the day, from Larwood bowling to a standard field, rose sharply and just missed Woodfull's head. From the other end, Voce opened with a full Bodyline attack to a concentrated leg side field, and no slip at all.

The pitch was not particularly fast, and the openers scored 22 runs against the onslaught, Bill Ponsford hit once on the hip, before Woodfull was out for 7. Jack Fingleton came in, with heavy padding covering his still recovering bruises from the previous game, and also took a blow to the hip. Fingleton played the hook shot as he had done with some success for NSW and the pair took the score to 65 before Ponsford, after having been struck again, on the rump turning to evade a ball aimed at him, was bowled by Larwood. Fingleton than fell to a leg side catch fending the ball away. Arthur Kippax was next to go, after being struck a glancing blow on the head, and once on the knuckles.

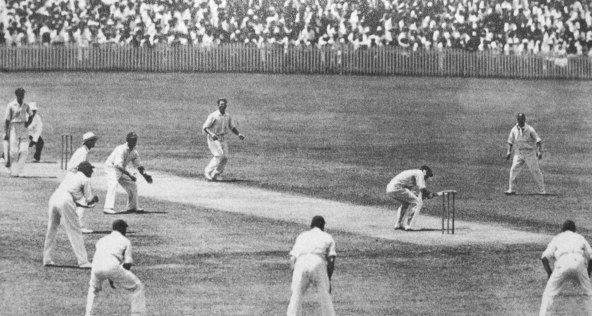

Australia had slumped to 87/4 and there was a deathly silence from the crowd of 40,000 spectators. Bob Wyatt, fielding near the boundary, was pelted with apple cores and orange peels by disgusted patrons.

Stan McCabe rubs his chest after being struck by a ball. |

But after Richardson was out on 49, Australia's tail collapsed quickly down to Tim Wall coming in at number 11, with the score 305/9. Bill O'Reilly, batting at number 10, had lasted only 8 balls, the first of which from Larwood had nearly taken off his head. There was to be no relaxing of Bodyline for the less skilled batsmen. But Wall defied the attack, refusing to get out for 33 minutes while he helped McCabe add another 55 runs, 51 of them off McCabe's bat. The 58,000-strong second day crowd stood and cheered McCabe off the field.

The English team boasted a strong batting lineup though, and after Bob Wyatt was out for 38, Herbe Sutcliffe and Wally Hammond took England to 252/1 at the end of the second day. Travelling home on the tram, the two umpires George Hele and George Borwick overheard many grumbled complaints from spectators about the Bodyline tactics. Discussing events that night, the umpires decided they were powerless to do anything to prevent Jardine's tactics, as there was no mandate within the Laws of Cricket to cover such a situation.

After the rest day, England carried their innings to 479/6 on 5 December. On the fourth day, 6 December, England were finally dismissed for 524, with a first innings lead of 164 runs.

Australia came in to face more rough treatment. Ponsford was cracked on the hand by Voce and ripped his gloves off in agony. Next ball he swayed out of the way of what he thought would be another bullet aimed at his body, only to see the ball smash into his leg stump. Larwood smashed Woodfull's stumps soon after and Australia were 10/2. McCabe, promoted to number 4, put together 51 runs with Fingleton. At 61, Hammond trapped McCabe lbw and had the incoming Richardson caught at slip the next ball. Wickets continued to fall and only the clock and a botched stumping attempt by keeper Les Ames let the Australians see through the day. They ended at 164/9, with the scores level and only one wicket in hand.

Only 100 or so showed up to witness the 10 balls bowled on the fifth day. Voce bowled O'Reilly with the ninth ball of the day, with no score added. After his outstanding batting performance, McCabe was given the chance to cause a stir with the ball, but Sutcliffe hit his first delivery for a comfortable single and the winning run. England had won by 10 wickets.

McCabe had been hit on the body by the ball four times, Fingleton eight. But the Australian Board of Control remained inactive. Harold Heydon, secretary of the NSW Cricket Association wrote Bill Jeanes in Adelaide, secretary of the Board of Control, warning that any repeat of the Bodyline tactics at the Adelaide Oval might be liable to cause public disorder. Future Governor-General of Australia Billy McKell urged Woodfull to retaliate against England's batsmen in kind. Woodfull refused point blank, and was called a "Puritan" by the editor of The Australian Cricketer for it.

The public could not stop talking about Bodyline. Cyril Ritchard, performing in Our Miss Gibbs at Her Majesty's Theatre in Sydney added a new verse to the show:

Now this new kind of cricket, takes courage to stick it,

There's bruises and fractures galore.

After kissing their wives, and insuring their lives,

Batsmen fearfully walk out to score.

With a prayer and a curse, they prepare for the hearse,

Undertakers look on with broad grins,

Oh, they'd be a lot calmer, in Ned Kelly's armour,

When Larwood, the wrecker, begins.

The Englishmen travelled on to Tasmania, where Jardine gave a brief interview for Reuters, indicating that he did not consider the fast leg theory bowling attack dangerous and that he hoped to continue to be successful with it. Jardine also wrote a letter to Billy Findlay, secretary of the MCC in London, stating that fast leg theory had come as an "unpleasant surprise to the old hands in Australia" and that the Australian newspapers were accusing England of bowling "at the man" rather than the wicket. Jardine wrote that it was nothing of the sort.

On the other hand, Plum Warner, the English team manager, was getting more concerned about Jardine's tactics. He also wrote back to Findlay, describing the hostile feeling the leg theory tactic was generating and fearing that it could cause a "terrible accident". To the Australian press, however, Warner was complicit in the blame. An article in The Referee criticised Warner's failure to censure Jardine and stop Bodyline. The article foreshadowed worse feelings to come: "He is, by his official indifference, helping to breed a feeling of bitterness, not only between the opposing teams, but between the peoples of the two countries of the Empire."

England played two matches against Tasmania, winning the first by an innings and 126 runs, and drawing the second, rain-soaked affair played either side of Christmas Day. Jardine had criticised the conditions in Hobart and generally made himself his usual unpleasant self. The Hobart Mercury called Jardine a "sulky schoolboy" and another paper stated Jardine would be remembered as "the undertaker and gravedigger of the traditions of English cricket".

As well as Bradman, veteran spinner Bert Ironmonger was back in the Australian side, and young Leo O'Brien made his debut; Ponsford, Kippax, and Nagel were left out. England made only one change from Sydney, bringing in Bill Bowes for Hedley Verity. England had thus dropped spin for an all-pace attack.

But off the field tensions were rising in the English camp. Jardine again approached Gubby Allen, who recorded the conversation in another letter to his parents. Jardine said, "I had a talk with the boys, Larwood and Voce, last night and they said it is quite absurd you not bowling bouncers: they say it is only because you are keen on your popularity." Allen responded indignantly that if it had only been about popularity he would have been bowling bouncers years ago, and that he had no intention of starting now. Jardine left it at that.

Woodfull won the toss again and elected to bat on a pitch that turned out to be far slower than anyone, particularly Jardine, had expected. His pacemen struggled to get any life from the ball, but still the Bodyline attack produced danger to the batsmen. Fingleton was struck on the knee, then the hand, the hip, a painful blow to the thigh which held up play for several minutes as he recovered, and then a crack on the thumb.

Woodfull was out with the score on 29 and, to the surprise of everyone, not least Bradman himself, debutant O'Brien was listed to come in at Bradman's usual number 3 position. He scored 10 before sacrificing himself in a run out to save Fingleton with the total at 67.

In strode Bradman to a massive ovation from the crowd. The cheering held up play for several minutes as Bill Bowes fiddled with field adjustments to avoid bowling with the crowd at full roar. Across the nation ears were pinned to radio sets, and at the ground the atmosphere of expectation was electric. Finally, Bradman would teach the English bowlers a lesson.

Don Bradman bowled off the first delivery he received in the series. |

Australia struggled to 194/7 by the end of the day. Fingleton, top scoring with 83 before being bowled by Allen, had a bruised right hand that would bother him for the next week. They reached a slow 228 the next day, as bouncing balls failed to rise off the slow pitch. Tim Wall and the wily Bill O'Rielly then proceeded to dismantle the until now formidable English batting, O'Reilly getting prodigious spin on the slow pitch. England fell to 161/9 by the end of the day.

In a New Year's Eve function hosted by the Victorian Cricket Association, Jardine gave a speech in which he expressed disappointment in his own poor batting performance that day - and also in the poor batting of his opposing captain, Bill Woodfull. New Year's Day was a rest day.

68,238 people packed into the MCG on 2 January, some of them queueing for over three hours to get in, breaking the record set only three days earlier. England added only 8 runs, giving Australia a first innings lead of 59.

Fingleton and O'Brien fell early, and Bradman walked in with the score at 27/2, facing a king pair. Larwood steamed in with the breeze to a full Bodyline field and let fly. Bradman connected cleanly and the crowd sighed in relief. Larwood and Bowes threw bouncers galore at him, but Bradman stuck with his tactic of quick footwork to position himself out of danger and hooked and cut the ball around the ground.

The wickets fell around him, however, and by the time Bradman reached 98, Bill O'Reilly fell to a catch off Wally Hammond and the veteran Bert Ironmonger, reputedly the worst batsmen in the world, was the only thing holding up the other end. The crowd, wishing for a century by Bradman, sat on the edge of their seats. Ironmonger had two balls to face from Hammond, who had captured three wickets already. He planted his bat firmly in front of the stumps as the first ball flew by just wide of it, then repeated the action to the frustration of the English slips with their gleaming eyes on the juicy edge of Ironmonger's bat.

Bradman now faced an over from Voce. The first five balls kept him pegged down, unable to score. Voce pitched the last ball short, Bradman rocked back on to his heels and pulled it majestically over midwicket into the outfield, then urged the aging Ironmonger to run the three hardest runs of his life. He had his century and the strike, and the adulation of the crowd who cheered for minutes.

Bradman added another two runs, but taking a quick single to retain the strike again, Ironmonger was too stretched to serve the cause again and was run out. Australia had scored 191, over half coming from Bradman's masterful 103, and had a lead of 250.

Sutcliffe and Leyland, promoted up from 5, took England to 43 without loss at the end of the day. On day 4, the cunning spin of O'Reilly and Ironmonger undid the English batsmen on the wearing pitch. England crashed to be all out for 139, and Australia won comfortably by 111 runs.

The crowd invaded the field and carried Woodfull off the ground in unbridled joy. Song broke out and hats were thrown in the air. Once the players had reached the safety of the dressing rooms, the chant went up, "We want Woodfull!" The captain dutifully appeared on the balcony above the gathered throng and gave a speech. Jardine also appeared on the balcony (only after some coaxing, by some accounts) and muttered the words, "Well, you have won. Why not go home?"

So what had become of England's devastating Bodyline attack? Everyone agreed that on a pitch this slow, spinners would take wickets faster than anything else. Jardine's choice of bowlers in these conditions lost him the game and levelled the series at 1-1.

Adelaide was abuzz with preparations for the third Test. Packed trains arrived every day for a week before the game; every hotel room in the city was booked out. Several thousand fans arrived at the Adelaide Oval days before the match to watch the English team practise their skills. They hurled abuse at Jardine, who cut the session short and demanded of the South Australia Cricket Association that the "display of hooliganism" be curbed at his team's next practice. The next day, police were duly standing guard, preventing any fans from watching the Englishmen.

Long queues of spectators waited to fill the Adelaide Oval to the tune of 37,000 people on the opening day, Friday the 13th of January. It was to be a bad omen.

Hedley Verity replaced Bill Bowes for England, balancing the pace attack with some spin, and left-handed Eddie Paynter replaced the solid but slow-scoring Nawab of Pataudi, with the hope of upsetting Australia's leg break spinners. The Australian team was unchanged from the Melbourne victory.

Jardine finally won the toss, and elected to bat on the Adelaide pitch famous for its geniality towards batsmen. Former Australia captain Clem Hill remarked, as the captains walked off the field, that it should be a close game. Jardine, overhearing the comment, retorted that Hill had clearly not heard who won the toss.

It soon became apparent that the pitch was not a typical Adelaide flat track, as balls kicked and lifted sharply and with fire in their bounce. England fell to 30/4 as Sutcliffe, Jardine, Hammond, and Ames went cheaply to the devilish pitch. Leyland and Wyatt then came together and built a 156-runs partnership to save the innings. That and Paynter's 77 took England to 236/7 at the close.

Bill Woodfull is struck over the heart by Larwood. |

Larwood steamed in and let a thunderbolt fly, missing Woodfull's head by a slim margin. Larwood's next ball flew off the pitch and thudded sickeningly into Woodfull's chest, directly over his heart. Woodfull dropped his bat and staggered away from the pitch. In the second of silence before a roar of disapproval rose from the crowd, Jardine yelled to Larwood, "Well bowled, Harold!"

And then the roar was upon them. Waves of sound crashed over the England players. Larwood was discomfited by the tumult; Wally Hammond called to reassure the bowler, "Don't take any notice of them," but his words were lost in the din.

Woodfull was hurt, but determined to continue. Play was held up for several minutes as he examined the bruise appearing on his chest. Jardine pointed out that Woodfull was welcome to retire hurt if he needed to, but Woodfull refused. It had been the last ball of Larwood's over, so Bradman now faced Allen. He played out the over, then Woodfull steeled himself to face Larwood again.

And Jardine chose that moment to set the Bodyline field for the first time in the match. As he called fielders across to the leg side, the crowd, already incensed, raised the volume of their catcalls and protests to a new level of fury.

Austalian selector Bill Johnson called it "the most unsportsmanlike act ever witnessed on an Australian cricket field."

Victorian Cricket Association president Canon Hughes was heard to say, "Cancel the remaining two Tests. Let England

take the Ashes for what they're worth." The crowd were so incensed that in retrospect it seems amazing that a riot

didn't break out. If one person had jumped the picket fence and rushed at the Englishmen, hundreds more would surely

have followed, and the mounted police would have been able to do precious little to prevent an ugly scene. As it was,

it was fortunate that Woodfull and Bradman managed to bat without suffering further injury, as if they had who knows

what sort of violence could have been done.

Bill Woodfull drops his bat after being hit again, with the Bodyline field in place. |

Ponsford's chosen method of dealing with Bodyline was to turn his back to balls aimed at him, and take the blows on his rump and back. He was thus struck at least a dozen times, but thankfully never by a ball rising high enough to reach his head. The crowd hooted and hurled abuse at the Englishmen. Woodfull was also hit a few more times, before finally playing on to Allen. He had weathered the storm for an hour and a half to compile 22 runs. Australia had sunk to 51/4.

Vic Richardson helped Ponsford see Australia through to stumps with a 58-run partnership as fans variously shouted expletives at Jardine, and calling comments, some of which have been recorded: "You Pommie bastard!" "D'you call this sport?!" "Why don't you play cricket, Jardine?!" and "Hey Larwood, bowl at the wicket, not his head!" Australia ended the day at 109/4, in serious trouble.

In the Australian dressing room, Woodfull had emerged from a shower and was standing with a towel around his waist when the English co-managers Plum Warner and Dick Palairet visited and expressed sympathy and concern for Woodfull's injury. It was the right thing to do and, as revealed later, Warner was not happy with Jardine's tactics and presumably was genuinely concerned for Woodfull's wellbeing. Woodfull, normally quietly spoken, reserved, and highly respected for his sense of propriety, had however had enough. He replied, in an outburst that has since become cricketing legend:

I don't want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not.Later writings by Fingleton and W. M. Rutledge of The Referee recorded that Woodfull continued: "This game is too good to be spoilt. It is time some people got out of it. The matter is in your hands, Mr Warner, and I have nothing further to say to you. Good afternoon." Warner, almost in tears, left without a word. When he returned to the England team and told Jardine what had passed, Jardine told him, "I couldn't care less."

Woodfull's remark was leaked to the press - who by is a mystery to this day. But it became public knowledge. Many Australian fans had felt up to now that if Australia's captain could put up with Bodyline, then perhaps their own outrage was too strong a reaction. But now they knew, Woodfull hated Bodyline too. This knowledge catalysed the feelings of the public.

It also finally pushed the Australian Board of Control into action. They asked Warner and Palairet to put an end to Bodyline. They replied that they couldn't, as they had no control over Jardine in matters occurring on the cricket field. The Board decided to escalate their action and send a cable to the MCC in England.

Sunday was a rest day, and play resumed on Monday, 16 January. Over 32,000 fans came to watch Ponsford and Richardson add another 22 runs before Richardson played on to Gubby Allen. Wicket-keeper Bert Oldfield joined Ponsford and they took Australia to 185/5 at lunch. After the break, Ponsford was out 15 short of a century and Clarrie Grimmet joined Oldfield at the crease. Grimmet scored 10 before giving a catch to Voce off Allen. Tim Wall came in at 212/7.

Bert Oldfield staggers away after being hit in the head by Larwood. |

The umpires and players raced to his side. Gubby Allen ran off the ground to get a jug of water and a towel. Bill Woodfull had been a guest in the Governor's box when the incident happened and, dressed in a business suit, he raced out of the box and strode out to the middle of the ground.

The crowd hooted and hollered as loudly as the record crowd two days earlier, and once again it was a miracle that an all-in riot did not break out. Men were jumping up and down, yelling obscenities, and waving their fists angrily. Policemen moved on to the ground, and some of the English players clearly eyed the stumps as possible defensive weapons. The South Australian Cricket Association office called Adelaide police headquarters and asked for reinforcements to be sent to the Oval.

Oldfeld's right frontal bone had been fractured and blood was trickling from the wound. He staggered to his feet and

was assisted from the ground by Woodfull, and was taken to hospital suffering from concussion and shock. Woodfull

later said he regretted not declaring the innings closed there, when he was on the ground, as a sign of protest.

But he didn't, and a stunned Bill O'Reilly staggered slowly to the middle to face the bowling.

Bert Oldfield clutches his fractured skull as he falls to the ground. |

Jardine again opened the English innings with Sutcliffe, Harlequin cap perched defiantly on his head. A fan called to Tim Wall, "Hit 'im on the bloody 'ead, Tim!" A groundsman was sweeping up some horse manure near the heavy roller, and someone yelled, "Take that back to Jardine!" When Jardine's bat broke and a new one was brought out to him, a fan yelled, "You won't need it, you bastard!" At the drinks break, Woodfull handed Jardine a drink and someone shouted, "Don't give him a drink! Let the bastard die of thirst!" And as Jardine tried to brush away some persistent flies that were bothering him, the shout rang out across the ground, "Leave our flies alone, Jardine! They're the only flamin' friends you've got here!"

Sutcliffe was out for 7 and England ended the infamous day at 85/1, 204 runs ahead. Some spectators hung around the ground to jeer the English team as they left for their hotel, but a police escort kept them safe from any violence. A placard advertising the evening edition of a newspaper screamed at them: PREMEDITATED BRUTALITY.

The Australian players placed all the blame on Jardine. Oldfield went so far as to issue a statement exonerating Larwood of any blame for the incident. A telling incident occurred when Jardine visited the Australian dressing room to seek an apology for one of them calling Larwood a "bastard" in his earshot. Vic Richardson answered the door and, after determining what Jardine wanted, turned to the team and said, "Hey, which of you bastards called Larwood a bastard instead of Jardine?"

With Vic Richardson keeping wicket in place of Oldfield, England progressed to 296/6 on the fourth day. On the fifth day, England pushed the lead over 500. At the fall of the 8th wicket, Jardine sent in Eddie Paynter, who had injured his ankle fielding and was limping badly, in to bat with a runner. A doctor had advised Paynter to stay off the ankle for a week, but Jardine insisted he bat to grind the Australians unnecessarily further into the dirt. Finally the innings ended at 412, a lead of 531 runs.

Fingleton made his second duck of the match for Australia, and Ponsford, elevated to number 3, was out soon after. Then Woodfull and Bradman put on an 88-run partnership, with Bradman scoring 66 of them in a sparkling display of batting that had the crowd cheering finally. But he was out, followed quickly by McCabe before stumps. The sixth day didn't last long, as Australia's tail - short a man with Oldfield unable to bat - collapsed, leaving Woodfull stranded carrying his bat on 73, and Australia losers by 338 runs. It was England's second greatest margin by runs over Australia, after the 675-run whitewash in Bradman's debut Test in 1928.

In post-match speeches to the remaining spectators, Woodfull said, "This great Empire game of ours teaches us to hope in defeat and congratulate the winners if they manage to pull off the victory. I want you to remember that it is not the individual but the team that wins the match." In stark contrast, Jardine said, "What I have to say is not worth listening to. Those of you who had seats got your money's worth - and then some."

After the game was over, Gubby Allen wrote in a letter to his parents, unearthed in 1992 after his death:

Douglas Jardine is loathed and, between you and me, rightly, more than any German who fought in any war. I am fed up with anything to do with cricket... He seems too damn stupid and he whines away if he doesn't have everything he wants... Some days I feel I should like to kill him and today is one of those days.

Bodyline bowling assumed such proportions as to menace best interests of game, making protection of body by batsmen the main consideration. Causing intensely bitter feeling between players as well as injury. In our opinion is unsportsmanlike. Unless stopped at once likely to upset friendly relations existing between Australia and England.To fully comprehend the enormity of these words, one must keep in mind the context of the times. This was 1933, when those crowds at the Adelaide Oval uniformly worse business suits and hats. Australia and England shared an affectionate bond as between parent and child, having supported one another during the horrors of World War I, and with the first rumblings of more trouble in Germany threatening to require another staunch loyalty in time of need. The prevailing attitude in English and Australian society, and especially within cricket, was one of fair play, decency, and civility. To call an opponent "unsportsmanlike" was worse than an accusation of cheating - it was dirty, rotten cheating.

Mindful of his duty to the press, Bill Jeanes of the South Australian Cricket Association summoned most of the journalists to the SACA offices that day and read them the cable. Jaws gaped as the pressmen absorbed what had been said. Reuters correspondent Gilbert Mant raced to the cables office and sent a summary to his office in London. Being sensational news of the first order, he sent it at urgent rate. It arrived on the Reuters desk in London within minutes, around 2am local time. The Australian Board had sent their cable at normal rate - it arrived at the MCC some ten hours after Reuters had the news.

Viscount Lewisham, president of the MCC, was roused from his sleep in the cold winter of London at 2:30am by reporters insistently asking for his reaction to news he would not hear until lunchtime. This left him ill-disposed to a positive reception to the cable, when it finally arrived in his hands. Combined with the fact that Australia were on their way to going 2-1 down in the series, and the use of that word "unsportsmanlike", drove most of the British press - and the MCC Board - to consider that the Australian Board were sore losers, exaggerators, and whiners.

Back in Australia, Jardine asked Gubby Allen if he'd seen the cable. "Yes, I have, and I think it's dreadful." Jardine despondently replied, "I know they'll let me down at Lord's." Allen said, "No, Douglas, you're wrong. No-one can call an Englishman unsporting and get away with it. They've lost the battle with the first shot they've fired." And a slow smile spread over Jardine's face as he realised Allen was right.

Just how much was at stake, not only in cricket, but beyond, was reflected in a letter Bill Woodfull wrote to the Australian Board: "Since entering Test cricket I have not been sure that it is for the good of the Empire that in times when England and Australia need to be pulling together that large sections of both countries are embittered."

The MCC Board argued over the response, letting Australia sweat for five long days before, on 23 January, the Australian Board received this:

We, Marylebone Cricket Club, deplore your cable. We deprecate your opinion that there has been unsportsmanlike play. We have fullest confidence in captain, team and managers, and are convinced that they would do nothing to infringe either the Laws of Cricket or the spirit of the game. We have no evidence that our confidence has been misplaced. Much as we regret accidents to Woodfull and Oldfield, we understand that in neither case was the bowler to blame. If the Australian Board of Control wish to propose a new law or rule it shall receive our careful consideration in due course. We hope the situation is not now as serious as your cable would seem to indicate, but if it is such as to jeopardise the good relations between English and Australian cricketers, and you consider it desirable to cancel the remainder of the programme, we would consent with great reluctance.Although Plum Warner had expressed his misgivings about Bodyline to Jardine, his letters back to MCC secretary Billy Findlay up to this point had not given any indication of the rift, leaving the MCC with the impression that Warner supported Jardine.

The Australian Board decided telephone was inadequate and called an emergency meeting at Sydney, which took time to organise because some members needed to make long rail journeys. They met on 30 January, now divided by the MCC's cable. The thought of cancelling the remainder of the tour appealed to some, but not the Queensland and NSW representatives who would be hosting the fourth and fifth Tests and expected revenue from them. After much debate, they sent the following to the MCC:

We, Australian Board of Control, appreciate your difficulty in dealing with matter raised in our cable without having seen the actual play. We unanimously regard bodyline bowling as adopted in some of the games in the present tour as being opposed to the spirit of cricket and unnecessarily dangerous to players. We are deeply concerned that the ideals of the game shall be protected, and have therefore appointd a committee to report on the action necessary to eliminate such bowling from all cricket in Australia as from beginning 1933-34 season. Will forward copy of committee's recommendation for your consideration, and, it is hoped, co-operation, as to its application in all cricket. We do not consider it necessary to cancel remainder of programme.The MCC replied on 2 February, eight days before the scheduled start of the fourth Test in Brisbane:

We, the Committee of the Marylebone Cricket Club, note with pleasure that you do not consider it necessary to cancel the remainder of programme, and that you are postponing the whole issue involved until after the present tour is completed. May we accept this as a clear indication that the good sportsmanship of our team is not in question? We are sure you will appreciate how impossible it would be to play any Test match in the spirit we all desire unless both sides were satisfied there was no reflection upon their sportsmanship. When your recommendation reaches us it shall receive our most careful consideration and will be submitted to the Imperial Cricket Conference.The Australian Board had backed down, but not far enough. Still that word "unsportsmanlike" was like a wall between the Boards. Jardine made his feelings known. If the Australian Board did not withdraw the accusation of unsporting behaviour, his team would not play the fourth Test.

Public feeling in both countries was running high, with most newspapers in England accusing Australians of being squealers and whiners, while those in Australia took offence at being called such. The editorial of The Australian Cricketer would have caused pale faces in the British Parliament: "And everyone knows to whom England would look if she was threatened in war again. Even the Germans have never pointed the finger of scorn at the Australians."

It was inevitable that senior Australian and British diplomats would become involved in the affair. It is known that the Australian Prime Minister's Department opened the file "748/1/291: English Cricket Team 1932" and the Dominions Office in London maintained file "F20436/2" containing discussions on Bodyline, but the contents of both these files have been lost to history.

The Governor of South Australia, Sir Alexander Hore-Ruthven, happened to be visiting England at the time of the third Test. His private secretary, back in Adelaide, cabled the Governor and urged him to speak to the Dominions Office in London. He visited James Henry Thomas, Secretary of State for the Dominions, in Downing Street on 1 February with Viscount Lewisham and three other MCC Board members in attendance. The next day - the same day as the MCC's last cable - Hore-Ruthven cabled his deputy in Adelaide that what happened in the cricket matches was unimportant compared to maintaining good relations between Australia and England, and that the sticking point, as far as England was concerned, was the accusation of unsportsmanlike conduct. He indicated that the MCC would make every effort to resolve the situation amicably, but only if that charge was withdrawn.

Hore-Ruthven also presented a plan to Thomas, to smooth ill-feeling amongst the public in England, which was running with the opinion that Australians were sore losers and whiners complaining about something for which they had no real reason to complain. Hore-Ruthven suggested that British newspapers be encouraged to present a more balanced point of view, indicating that the Australians felt rightly aggrieved at what was happening to their batsmen. Such an indication would reduce tempers in Australia at having their opinions considered worthless by the British. Hore-Ruthven concluded with a carefully veiled threat: "That feeling rankles even to the extent of reluctance to buy British goods, which business men inform me is going on to a certain extent in [Adelaide] today."

As Dominions Secretary, Thomas could not ignore the possibility of harmed trade relations between England and Australia. He passed the comments on to Viscount Hailsham, Leader of the House of Lords, Secretary of State for War (in which role he would have had thoughts of strained military alliance weighing heavily on his mind), and president-elect of the MCC. And so the matter entered the British Parliament. In meetings between senior government ministers and the MCC, the government impressed upon the cricket club the fact that matters of state must take precedence over matters of sport, and that this Bodyline affair must be settled with Australia amicably.

Back in Australia, the increasingly desperate Plum Warner sent a telegram to Ernest Crutchley, head of the British Mission in Canberra, urging him to approach the Australian Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons, to see if he could bring some pressure to bear on resolving the issue. Crutchley telephoned Lyons and outlined the concerns that were beginning to cause dangerous cracks in the British Empire. Lyons in turn contacted Allen Robertson, chairman of the Australian Board of Control, and stressed to him the importance of resolving the dispute, given Australia's then economic dependence on England. It was thus the insistence of none other than the Australian Prime Minister that the Board withdraw the charge of "unsportsmanlike".

Finally, on 8 February, with the fourth Test scheduled to begin in just two days but the English team packed and ready to go home, the Australian Board cabled the MCC:

We do not regard the sportsmanship of your team as being in question. Our position was fully considered at the recent meeting in Sydney and is as indicated in our cable of January 30. It is the particular class of bowling referred to therein which we consider is not in the best interests of cricket, and in this view we understand we are supported by many eminent English cricketers. We join heartily with you in hoping that the remaining Tests will be played with the traditional good feeling.So the accusation was withdrawn, but on the understanding that Bodyline bowling would later be looked at in an official capacity as "not in the best interests of cricket". And evidence was mounting in the Australian Board's favour. Amateurs and junior cricketers across Australia were copying the Bodyline tactics they saw in the international games, with predictable results. Games in Darwin and Adelaide devolved into all-in brawls as batsmen were targeted and battered. The NSW ambulance service reported serious cricketing injuries had quadrupled. The NSWCA issued a memo strongly discouraging Bodyline in minor cricket matches, and the SACA banned it completely.

In Brisbane, Larwood, Voce, Bill Bowes, and Morris Leyland learnt just how high feelings were running against Bodyline. Drinking in the bar of their hotel, they were apporached by a rough looking man who wanted to talk to them about Bodyline. Larwood invited the man to sit and have a drink with them, but said he didn't want to discuss cricket. The man pulled out a revolver, slammed it on the bar, and said, "This'll probably make you." Larwood carefully called over the much bigger Voce, who suggested the man put the gun away. When he refused, Voce hit him, prompting everyone to flee the bar.

Meanwhile, poor Plum Warner was falling apart. The speech he gave at a reception in Brisbane before the Queensland match included the statements:

I pray for peace as much as any statesman ever prayed for peace... Anything that ruffles the calm surface of English and Australian cricket affectes cricket all over the world. I say from the bottom of my heart that England and Australia in cricket must never drift away from each other.And in a letter to his wife, written the day the Australian Board's defusing cable was sent two days before the fourth Test:

Nothing can compensate me for the moral and intellectual damage which I have suffered on this tour... DRJ must not captain again. He is most ingracious, rude and suspects all. He really is a very curious character and varies like a barometer. He is very efficient but inconsistent in his character and no leader. I ought to get a prize for patience and tact and good temper if not a knighthood! 75% of the trouble is due to DRJ's personality. We all think that. DRJ has almost made me hate cricket. He makes it war. I do hope the Test will go happily. I rather dread it.For the fourth Test, Voce had to be left out because of influenza, and the leg spinner Tommy Mitchell came in for England, meaning any Bodyline would be relying on Larwood alone. For Australia, Hammy Love came in to replace the recuperating Oldfield as wicket-keeper, and left-handed batsmen Len Darling and Ernie Bromley came in for Jack Fingleton and spinner Clarrie Grimmett. This left Australia with only three specialist bowlers and seven batsmen - a risky strategy.

Bill Woodfull ducks a ball, Larwood bowling with the full Bodyline field. |

Having fielded all day in the enervating heat and humidity, many of the English players were looking sickly, Gubby Allen in particular. They awoke in sweat-soaked sheets to another steaming day. Eddie Paynter confessed to feeling too ill to play, and twelfth man Freddie Brown took his place in the field for England. Paynter's temperature was taken and found to be a raging fever of 102°F (38.9°C). He was taken to Brisbane General Hospital and diagnosed with tonsillitis. Jardine expressed his displeasure that Paynter might have felt his illness coming on the day before and mentioned it before he had been selected on the team. Now England were a batsman down.

29,000 crushed into the Gabba ground in Brisbane, dripping with sweat, but expecting a Bradman century and a massive total by Australia as England toiled again in the field. But it was not to be: Larwood bowled Bradman, stepping back to leg to cut a ball pitched on leg stump, for 76, after only 13 had been added to the overnight score. He bowled Ponsford three runs later, puling Australia back to 267/5. The tail batted fitfully, taking Australia to 340 - measly-looking against their overnight position. Jardine and Sutcliffe then took England to 99/0 at the end of a second draining day.

The tide had turned from Australian dominance to about level, and both teams were happy for the rest day Sunday. Monday dawned the hottest day of the year in Brisbane. Jardine fell to O'Reilly's spin with England at 114, then wickets fell at regular intervals: 157/2, 165/3, 188/4, 198/5. Australia was beginning to dominate.

Bill Voce and Eddie Paynter were listening to the game in Paynter's hospital room, where he had spent most of the second day's play and all of the rest day. Paynter was groggy, but aware enough to know his team was in trouble. He asked Voce to go get a taxi and climbed into his dressing gown. A nurse tried to stop him, but Paynter bullied past her and outside, with the nurse declaring neither she nor Paynter's doctor could be held responsible if he left. Paynter and Voce arrived at the Gabba dressing room to a surprised looking Jardine. No sooner had Paynter strapped on his batting pads than Gubby Allen was out and England struggling at 216/6.

Eddie Paynter bats after leaving a hospital bed to save England's innings. |

On 24 not out, Paynter staggered off the field, changed into pyjamas and a dressing gown in the England dressing room, and was escorted back to hospital where he dropped into a solid sleep. Even with this brave resistance, Australia looked to have a handy first innings lead and the upper hand, with England batting last.

Paynter awoke the next day feeling somewhat better. He later said he felt that he had sweated out the fever by playing this innings. He returned to the Gabba and with Verity defied the Australians further. He had to take brief breaks to down pills and gargle with disinfectant, but batted courageously on. The pair took England to 300, and Paynter was cheered by the crowd when he reached his 50. Still, in the incredible heat, they batted on: 320, 330, 340. They took the lead off Australia and kept going. Finally, at 356, Paynter lofted a drive off Ironmonger and Richardson held the catch. Having scored 83 runs by sheer willpower from his sickbed and saved England's sinking innings, Paynter was clapped off the ground by the Australian players.

Four balls later, O'Reilly trapped Tommy Mitchell lbw and England's innings was over, with a lead of 16 runs. Paynter re-emerged with the England team to field, to good-natured cheers, but didn't last long before he returned to hospital and Freddie Brown replaced him. The entire atmosphere of the game could not have been more different to Adelaide, as Larwood struggled in the heat and most of his bouncers were smashed away through the leg side for runs, to the delight of the happy crowd.

But wickets fell steadily, and by stumps Australia had lost Richardson (32), Bradman (24), Ponsford (0), and Woodfull (19), leaving them 91/4. But McCabe and the promising young Darling were still in and could pile on the runs. And almost any lead might allow Ironmonger to rip through the fourth innings on a wearing pitch.

So Australia started day 5 with at least an even hope of winning the match. But it was dashed as the last 6 wickets fell for only 67 runs, giving Australia a precarious lead of only 159. If England could score 160 runs, they would take an unassailable 3-1 lead in the series and regain the Ashes.

Sutcliffe fell at 5 to Tim Wall, and the fans salivated at the thought of an English collapse. But it was not to be. Jardine and Leyland took the total to 78, then Hammond joined Leyland and England were a very comfortable 107/2 at stumps.

But there was a final twist as day 6 dawned, grey and overcast. A light rain fell as England picked up, requiring just 53 runs to secure the Ashes. Hammond fell at 118, then Leyland at 138. With 22 runs to go, Eddie Paynter strode to the crease to join Les Ames. The rain began to intensify, and lunch was approaching. It was now or never. If they couldn't secure the win by lunchtime, the game might well be called off because of the weather and drawn, leaving Australia a chance to level the series and retain the Ashes.

Ames and Paynter chased the runs, thrashing the ball around. At 156, four runs short of victory, the wet ball slipped from McCabe's bowling hand and presented Paynter with a full toss. Paynter launched into a hook and cracked the ball over the fence and out of the ground as the clouds burst and twelve hours of non-stop rain deluged Brisbane. Having risen from his hospital bed, and at the last possible minute, Eddie Paynter scored the runs that won England the Ashes.

Larwood recorded in his later book that he asked Jardine if he could be excused from this game. Jardine squashed his thumb on the table and twisted it as he refused, "We've got the bastards down there, and we'll keep them there."

Jardine lost his fourth toss of the series and Woodfull elected to bat again. Larwood had Richardson caught by Jardine at gully on the fifth ball of the match, but from there Australia consolidated as Bradman scored 48, O'Brien 61, McCabe 73. Bodyline was more in evidence than in Brisbane, with Woodfull again hit several times on the back as he continued to deal with balls aimed at him by turning his back to them. And when Oldfield came in, looking nervous, Jardine laid in with the full Bodyline field and Larwood steaming in at him. Oldfield survived unscathed, luckily, and Australia ended the day at a strong 296/5 with Darling looking good on 66 not out.

Darling continued on to 85 the next day, and Oldfield received stirring applause for his 52. England finally dismissed Australia for their series-best innings of 435. Harry Alexander, an aggressive bowler nicknamed "Bull", tried his hardest to make an impression on the English top order. But when he asked his captain for an extra fielder at square leg, Woodfull refused: "No Harry. Too much like Bodyline."

Jardine went cheaply, but by the time Sutcliffe also succumbed to O'Reilly, the score was 153/2. With only a few balls left, Jardine ordered Larwood in as nightwatchman, to the annoyance of the bowler who was still worn out after two days of bowling. Larwood snatched his bat and stormed out to the middle, telling Les Ames as he left, "Get your bat ready, Les, becuse I'm going to get myself out." Larwood smashed the ball recklessly, but survived on 5 runs overnight.

Still unhappy the next day, Larwood swung with abandon. Luck was on his side and he accumulated runs. By the time he reached 50, he had finally settled down and begun to play an innings. Wally Hammond was out for 101, and Leyland joined Larwood at 245/3. They took England to 310 before Larwood, on 98 and looking at a maiden Test century, mistimed a drive and sent an easy catch to Ironmonger at mid on. For this brave display of batting, the Sydney crowd was willing to forgive hs hostile bowling, and they rose to applaud him off the field.

With 51 from Wyatt and Gubby Allen scoring well in the tail, England finished the third day at 418/8, just 17 runs behind. The next day was the rest Sunday, and on Monday Allen helped England reach 454 all out. Australia started disastrouly, with Richardson hit on the thumb and caught second ball, giving him a pair, having faced only 7 balls in his two innings.

Bradman came in, and Jardine switched to the Bodyline field. Larwood hit Woodfull between the shoulderblades, causing a delay as he recovered, then soon after hit him on the thigh. Then Voce hit him on the shoulder. But bravely the captain batted on. At the other end, Bradman was peppered by short stuff too. But he had made a personal vow not to get hit above the waist by Bodyline bowling, and he remained the only Australian batsman so far to have avoided that fate. Watching the game, Jack Fingleton said that "Larwood was anxious to claim a hit on Bradman" and decided the bowler was uninterested in hitting Bradman's wicket. Bradman backed away, ducked, weaved, but Larwood chased him and finally connected. The ball smacked into Bradman's left upper arm, causing him to drop his bat.

With Bradman and Woodfull taking Australia past 100, the fans' hopes were suddenly kindled as Larwood pulled up short with a foot injury. He could barely walk, and wanted to leave the field, but Jardine yelled at him in a heated exchange and forced him to finish his over. Unable to run up, Larwood stood dejectedly at the crease and rolled his arm over, giving Woodfull five slow deliveries. Free to swat them to the boundary, Woodfull sportingly blocked the balls and gently patted them back to Larwood.

Having finished the over, Larwood pleaded with his captain, "I can't run. I'm useless. I'll have to go off."

Jardine snapped back, "Field at cover point. There's a man covering you there. You can't go off while this little bastard's in." Referring of course to Bradman.

At 115, with Bradman having scored 71, Verity slipped a ball past the defence weakened by the habit of stepping away from his stumps, and Bradman was bowled. Jardine called to Larwood, indicating he could go now. So Larwood and Bradman walked off side by side, neither looking at the other.

The rest of the Australians crumbled as Verity took 5/33. The total was only 182, giving England a target of 164 to win. Jardine, opening this time with Wyatt, took them to 11/0 at the end of play. On the fifth day, Jardine and Leyland fell to the canny Ironmonger with the score on 34, and the small crowd waited expectantly for a bowling miracle that never came. Wyatt and Hammond knocked off the runs, taking England to an 8 wicket victory and 4-1 dominance of the series.

Bruised and battered in every game, Bill Woodfull was given three rousing cheers in the Australian dressing room by his team, and then, ever the gentleman, walked across to the English dressing room to congratulate Jardine.

At the start of the English summer of 1933, the tide of opinion in England still believed that Bodyline was harmless and the Australians were squealers, upset at having been outplayed. As the summer wore on, that tide would be turned.

On 28 April, 1933, the Australian Board of Control had cabled a proposed rule alteration to the MCC. They proposed introducing a law that would require an umpire, if he considered a ball to be bowled at the batsmen with deliberate intent to intimidate or injure, to call no ball and warn the captain that another offence would result in the bowler being suspended. After a long wait, on 12 June, the MCC replied with a lengthy cable stating that the proposed rule was unworkable as it required impossible judgment on the part of the umpire and gave the umpire dangerous powers. The cable also stated that the MCC objected to use of the word "bodyline" as it implied a deliberate attack against the batsman's body, which it denied had ever taken place. That batsmen were being hit was, the MCC said, their own fault. As a final slap in the face, the MCC stated that the behaviour of the crowds in Australia - yelling abuse at the English players - was "thoroughly objectionable", and that apparently the Australian Board had done nothing to bring the crowds under control, which was regarded as a serious lack of consideration towards the English touring party. If the behaviour of Australian crowds was not controlled, the MCC concluded that "it is difficult to see how the continuance of representative matches can serve the best interests of the game." This stunning attack left the Australian Board speechless - they were not to communicate with the MCC again for another three months.

Meanwhile, the West Indies were in England preparing for three Test matches. In the first Test, at Lord's, King George V was in attendance. He had a private conference with Jardine, and then later inquired with some concern of Gubby Allen what had really gone on in Australia. Was the King concerned about relations between England and Australia?

In the second Test, at Old Trafford in Manchester, the West Indies unleashed Bodyline on the English team. The great West Indian fast bowler Learie Constantine hit Wally Hammond on the shoulder blade, then on the chin, forcing him to retire for stitches. Jardine, in scoring his only Test century, was hit numerous times, but took it stoically and never complained. But Hammond was later to say, "We started it, and we had it coming to us." Herb Sutcliffe, in Constantines's firing line, was distinctly unhappy, and Bob Wyatt and Les Ames suffered telling blows as well.

The English public, seeing what Bodyline was like firsthand for the first time, were not happy either. Angry letters poured into newspapers, deploring the tactic. Plum Warner finally had ammunition for his long-standing displeasure and wrote a long letter to the Telegraph, stating that what England was now suffering at the hands of the West Indies was in fact mild compared to what Larwood and Voce, considerably faster than Constantine, had dished out in Australia. "To suggest that the Australians are squealers is unfair to men with their record on the battlefield and on the cricket field."

And across England Bodyline was the vogue in first-class cricket too. In a West Indian tour match against the MCC, Constantine hit Joe Hulme in the ribs and thighs four balls in a row. In the same game, Bill Bowes hit West Indian batsman George Headley in the chest, knocking him unconscious for a desperate five minutes. Bowes also hit English batsmen in county games, knocking Frank Watson senseless with a blow to the head that had the charged crowd screaming, "Killer!" Half a dozen others suffered serious injuries, including Walter Keeton struck on the cheekbone and knocked to the ground. In the Oxford versus Cambridge match, Ken Farnes hit Oxford's P.C. Oldfield on the jaw, David Townsend on the neck, Alan Melville in the ribs, and struck other batsmen numerous times.

At Nottingham, Leicestershire's Haydon Smith decided to retaliate against Larwood and Voce's bowling by letting their captain Arthur Carr have a taste. Carr was hit in the body, narrowly avoided being struck in the face twice, and ended up severely shaken. And so the man who had helped Jardine and his fast bowlers invent Bodyline in 1930 finally saw firsthand what it was like. He approached Leicestershire's captain E.W. Dawson, and the two of them decided that "this sort of thing was not good enough and we mutually agreed that we would not stand for it." Carr then released a statement to the press:

Somebody is going to be killed if this sort of bowling continues, and Mr Dawson and myself considered that the game would be much more pleasant if it is stopped. Sooner or later something will have to be done so why not do it now?Dr Robbie Macdonald, an Australian living in England who had represented the Australian Board several times at Imperial Cricket Conference meetings, had been quietly working behind the scenes to make the Board's feelings more clear to the MCC. Late in the English summer of 1933, he hinted quite strongly to the MCC that the planned Australian tour of England in 1934 would be conditional on an unhindered guarantee of no Bodyline bowling. The Board followed up with a cable on 22 September, stating essentially that in very couched and diplomatic language - which also included a deferential promise to look into the issue of Australian crowd behaviour.

A few cables flew back and forth in similarly guarded language. The main sticking point was the insistence of some of the Australians that there be an unequivocal guarantee of no Bodyline. The MCC were not keen on such a guarantee, but would extend a gentleman's agreement to essentially the same effect. Dr Macdonald, in his important role as a diplomatic facilitator, smoothed over this difference by insisting to the Australian Board that the MCC really meant it.

On 23 November, a full meeting of the Board of Control of Test Matches at Home, the Advisory County Cricket Committee, and 14 of the county team captains (plus the other three by proxy) convened at Lord's. Before the English summer only one county captain had expressed any concern at all about Bodyline. Now, having seen it in action against their own players, 14 of them voted in favour of an agreement to ban Bodyline in county cricket. However, they stopped short of writing in a change to the Laws of Cricket.

The MCC cabled the Australian Board that the agreement not to bowl Bodyline existed, but the Laws had not been changed. This was enough, and the Board cabled back that they would be happy to tour England in 1934 on that understanding.

Jardine had resigned as captain and would not be playing for England. The MCC decided Larwood would be the scapegoat for Bodyline. They prepared a statement for Larwood to sign, apologising for his bowling on the Australian tour. Larwood, incredulous at being asked to apologise for what he considered to have been doing his duty by following Jardine's orders, refused. He never played for England again. Now vilified in his own country and becoming more bitter as the years passed, Larwood eventually took the advice of a friend and emigrated to Australia in 1950. The Australian public placed the blame for Bodyline squarely on Jardine's shoulders, and welcomed Larwood willingly. Larwood lived out the rest of his days, finally happy to have found a place that didn't blame him.

A later change, around 1960, introduced a rule that no more than two fielders (apart from the wicket-keeper) may be behind the batsman's popping crease on the leg side at the time of delivery. This weakened any temptation to aim at batsmen, as it removed the possibility of multiple close catchers on the leg side, which was a key feature of Bodyline.

Finally, in the 1990s, a rule was introduced to limit the number of fast short-pitched balls bowled in an over. In Test cricket now, any balls bouncing above shoulder height beyond the first two in an over are no balls, regardless of aim or intent.

Previous: The First Tests | Next: The Post-War Period